UNC-Chapel Hill Professor Emeritus William Leuchtenburg celebrated his 102nd birthday recently. He was born on September 28, 1922.

UNC-Chapel Hill Professor Emeritus William Leuchtenburg celebrated his 102nd birthday recently. He was born on September 28, 1922.

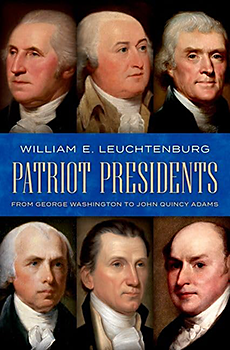

A few weeks ago, Oxford University Press released his latest book, “Patriot Presidents: From George Washington to John Quincy Adams.”

Leuchtenburg earned his BA from Cornell and his PhD in History in 1951 from Columbia, where he taught before joining the history department at UNC-Chapel Hill in 1982.

According to the department, Leuchtenburg became a leading scholar of 20th century U.S. history and the American presidency and the preeminent expert on FDR, writing profoundly influential books including “The Perils of Prosperity, 1914–32” (1958).

His “Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal, 1932-1940” (1963) won the prestigious Bancroft Prize and the Francis Parkman Prize. Sixty years later, it remains the best single volume treatment of the subject.

His later publications have constantly enhanced his historical influence and stature. These works include “In the Shadow of FDR: From Harry Truman to Ronald Reagan” (updated and subtitled From Harry Truman to Barack Obama, 2009); “The Supreme Court Reborn: The Constitutional Revolution in the Age of Roosevelt” (1996); “The FDRYears: On Roosevelt and His Legacy (1997); The White House Looks South: Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harry S. Truman, Lyndon B. Johnson”(2005); and “The American President: From Teddy Roosevelt to Bill Clinton (2015).”

In his latest book, “Patriot Presidents,” Leuchtenburg, with the help of his spouse, editor and writing partner, Jean Anne Leuchtenburg, sets out to narrate and explain the record of the first six presidents, George Washington, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, James Monroe, and John Quincy Adams, our founding fathers.

The book’s opening chapter on the Constitutional Convention of 1787 analyzes how the founding fathers created a unique institution, the presidency.

They were determined to authorize an effective chief executive but cautious of monarchy. The presidency that developed over the next generation was fashioned less by the clauses in the Constitution than by the way that the first presidents responded to challenges.

Chapter 1. “The Constitutional Convention of 1787: Framing the Presidency” explains why James Madison is called the father of the Constitution and answers the question of why the convention made the critical move in taking the choice of the president from Congress and vesting it in an electoral college

Chapter 2. “George Washington: Launching the Presidency” focuses on George Washington, who recognized that the American president is simultaneously the head of state and the chief executive.

It also considers the emergence of political parties, the Republican and the Federalist, despite widespread hostility to factions.

Chapter 3. “John Adams: Preserving the Republic in Wartime.” Although Adams had to cope with war hysteria, he won the hearts of peace-loving Americans by opposing the efforts of Federalists in Congress to create a provisional army.

The chapter then elaborates on the last moments of Adams’s regime, when he reflected that neither he nor the country had a party, unlike Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton.

Chapter 4. “Thomas Jefferson: Limiting the Government while Creating an Empire” shows how Jefferson’s presidency expanded civil liberties, notably freedom of speech and freedom of worship.

The chapter expounds on how Jefferson undid the seamiest transactions of the Adams presidency and altered the style of the national government by replacing the rococo excess of the Federalists with Doric simplicity.

Chapter 5. “James Madison: Leading the Nation through the Perilous War of 1812.” Leuchtenburg explains how James Madison led the nation into and through the War of 1812. Madison took power at a time of a weakened presidency, but English and French depredations on US commerce moved him to exert bold leadership.

In the ensuing war, the United States suffered numerous setbacks, including the burning of the nation’s capital, and the war ended as a stalemate, but Americans chose to view it as a triumph, especially after Andrew Jackson’s success in New Orleans.

Chapter 6. “James Monroe: Enunciating a Doctrine for the Ages.” Even though Monroe was scrupulously respectful of the curbs on executive powers mandated by the Constitution, he made a considerable impression on the institution of the American presidency. He made his greatest mark in foreign affairs by enunciating the Monroe Doctrine.

Chapter 7. “John Quincy Adams: Advocating Activist Government.” Unlike predecessors who quailed at the assertion of federal authority that lacked clear constitutional sanction, Adams boldly declared that liberty is power, and advocated an ambitious program of internal improvements.

The Adams program, in fact, was the forerunner of later initiatives such as the Square Deal, the New Deal, the Great Society, and Bidenomics.

A reader of Leuchtenburg’s remarkable book will ask, What in the world is this 102 year man going to do next?

Editor’s note: D.G. Martin, a retired lawyer, served as UNC-System’s vice president for public affairs and hosted PBS-NC’s North Carolina Bookwatch. Book Cover Courtesy of D.G Martin

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?