We know exactly what DTC is even if we do not recognize the acronym.

DTC stands for direct-to-consumer advertising, a term that generally refers to the ubiquitous drug ads brought to us by Big Pharma encouraging us to ask our doctors if “Make me feel better” is right for us. DTC is what informs us — and our naturally curious children — about “erections lasting longer than four hours,” constipation caused by opioid use, brand name surgically implanted mechanical joints and painful sex after menopause. Not to mention all manner of unpleasant digestive disorders, sleep interruptions and debilitating mental-health conditions.

People suffering such conditions are generally depicted looking sad and pained, but after taking “Make me feel better,” they are frolicking in impossibly green meadows holding hands with their loved ones and trailed by happy dogs. DTC refers to drugs sold by prescription only and not to the ones we can buy over the counter, such as aspirin.

Who knew? And, frankly, who wants to know and talk about all this outside the privacy of your doctor’s office?

An entire generation of Americans has grown up since 1997, when the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved DTC for prescription drugs. It has done so presumably thinking DTC is the norm, but it is not. The United States is one of only three Western nations that allow this sort of DTC advertising. The others are New Zealand, a nation with half the population of North Carolina and Brazil, which strictly limits such advertising. Apparently, no other Western nations think pharmaceutical DTC advertising is such a great idea.

Neither does Minnesota Senator Al Franken, he of Saturday Night Live fame who morphed into politics and was elected to the United States Senate by just more than 300 votes. Franken has filed a bill to eliminate tax breaks taken by pharmaceutical advertisers and which make all those billions spent on DTC advertising more palatable. Franken is not alone. You are totally safe in betting the farm that Big Parma will oppose that bill with big vigor — and big money.

Late last year, the American Medical Association called for a ban on DTC advertising, citing its dramatic growth and suggesting the ads are driving consumer demand for expensive drugs when less expensive ones are equally or more effective and when the drugs in question may not be appropriate at all.

Part of the concern is that DTC advertising has ballooned since the FDA initially okayed it, with as many as 80 ads an hour and annual spending reaching $5.4B — yes, billion — last year, according to Kantar Media. All that spending, even with tax breaks, amounts to a lot of money, which means drugs cost more. The New York Times reports that one heavily advertised drug to fight Hepatitis C costs a whopping $1,100 per pill. Dr. Patrice Davis, incoming chair of the American Medical Association, expresses the problem this way, “Patient care can be compromised and delayed when prescription drugs are unaffordable and subject to coverage limitations by the patient’s health plan. In a worst-case scenario, patients forego necessary treatments when drugs are too expensive.”

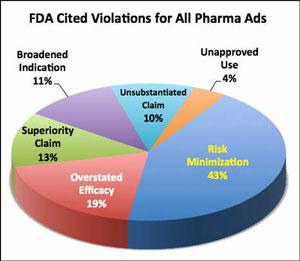

In addition, the FDA’s Deputy Commissioner Dr. Janet Woodcock says, “Much of our compliance and enforcement activity is spent trying to ensure that companies don’t low-ball risks in the ad and provide inflated expectations of benefit.”

FDA physician surveys find that docs, 78 percent of them, think patients have a fairly solid understanding of the benefits of

DTC advertised drugs but a minority of 40 percent believe their patients have a grasp of risks, and 65 percent think their patients are confused about benefits and risks of drugs advertised by people frolicking in too green fields.

Put me in that category.

Those surveys have also found that doctors feel pressured by patients to whip out their prescription pads to prescribe the drug du jour, whether it fits a need or not. Several of my own docs have confirmed such pressure from patients who have seen DTC ads and who may have done Internet research themselves.

Opinions are not all negative.

The AMA says docs also tell them that DTC advertising has made some patients both more knowledgeable and more thoughtful about treatment options for what ails them. Some also say that DTC advertising has engaged more patients in making their own health care decisions. In addition, surveys indicate that DTC ads encourage discussions between doctors and patients on health care issues.

On balance, Senator Franken’s effort to slow down DTC advertising feels right. It is neither all bad nor all good, but a thoughtful look at what only the United States and one other tiny nation have embraced full bore is in order.

Maybe I am just tired of discussing bodily functions in Technicolor 24/7.

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?