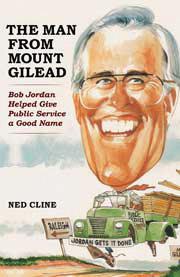

Hard to find dirt on this politician

Every politician is the object of critical, unfriendly, and just plain bad com-ments. That is the rule.

But retired journalist and biographer Ned Cline may have found an exception.

He had to look long and hard to find any dirt on the subject of his latest book, The Man from Mount Gilead: Bob Jordan Helped Give Public Service a Good Name.

The closest thing to dirt about Jordan was during his campaign against incumbent governor Jim Martin in 1988. His consultants prepared a television ad that showed a bunch of real monkeys dressed in tuxedos but acting wildly.

They were, the ad implied, as ineffective as Governor Martin’s staff. It was funny and made an important point. But in the minds of some people, it was tasteless and un-fair. So, Jordan quickly pulled the ad.

Democratic Party Executive Director Ken Eudy had pushed for more attack ads and told Cline later, “Bob just didn’t have the stomach for that kind of campaigning. He would have been a great governor, but he was not a great campaigner on things like that. I don’t think he wanted to win that badly.”

Cline found one other time during the 1988 campaign when Jordan drew a few critical remarks. Explaining to black newspaper editors why he was not more forthcoming on some issues that were important to their readers, Jordan said, “I can’t publicly say some of the things you are asking because I need all the votes I can get, including the redneck votes in Eastern North Carolina.”

White conservatives, racial minorities, and Republicans jumped on Jordan for a few days.

But for Jordan, “redneck” was not necessarily a negative term. He identified with the farmers and working people like many of his friends in Montgomery County. In this respect Cline compares Jordan to Jim Hunt. “Both are products of a rural upbringing.”

Both thought their rural and small town upbringings were assets, not liabili-ties. They understood and appreciated the conservative attitudes, as well as the aspirations and challenges, of the people who were their friends, schoolmates, and co-workers when they were growing up. Those kinds of connections can be important advantages for political leaders who otherwise might be too liberal for the North Carolina conservative rural and small town voters.

Cline points out that Jordan and former governor Jim Hunt have much else in common. In addition to their rural upbringing, “…Both are top graduates of N.C. State University, where their devotion and loyalty are legendary. Both have served the state in multiple capacities of public service….Both were raised by highly respected, fiscally conservative, yet socially conscious parents… who focused on the goodness of people and taught their children to focus on the do-able rather than negatively on the difficult.”

The differences, Cline says, are in approach, with Hunt “more like a hard changing fullback crashing through the line just to prove he can score while Jordan, more like a nimble quarterback, is more methodical in scoring by avoid-ing tacklers rather than knocking them down.”

Jordan and Hunt were political allies, but Cline’s book leaves its readers speculating whether or not they might have found themselves running against each other for governor in 1992 if Jordan passed by the 1988 campaign and waited until 1992 to make his run for governor.

Hunt told Cline, “I really don’t know what I would have done if (Jordan) had waited until then and run…But it would have been hard for me to be a can-didate if Bob Jordan were a candidate.”

We may be left to wonder about that possible 1992 contest, but Cline’s cataloguing of Jordan’s contributions to political and public life leaves no doubt that his service and example have been a great blessing to North Carolina.

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?